Are you ready with your SBOM ? Think again !

Security and Integrity of software supply chain is one of the fundamental requirements in the overall assessment of cybersecurity. The first step in securing software supply chain is the ability to provide complete, accurate and audit-able record of every dependency baked into building a deliverable software product or as generally referred to as Software Bill-of-Material (SBOM). Well, it also has an executive status now!

Just for the clarity: Software supply chain security is in general very broad in scope and referred in different contexts including technical, procedural and regulatory aspects. In this blog, references to the software supply-chain (SSC) is limited to the scope for container based micro-services in DevSecOps. Also, the whole SBOM generation is not new for micro-services, there are few great tools and automations already available and used in practiced. In this blog, the sincere attempt is to take a step-back to reflect on current path.

What is Bill-of-Material?

Think of the time when you go for the grocery shopping. When you picked any processed and packaged food item, you have no idea what ingredients went into that product. And you are allergic to certain food items, so you want to be absoutely sure that food item does not include those allergic items. Another important thing is – during processing the ingredients gets transformed in shape and size and color and everything (grain to powder or fruit to cyrup, and likewise), so just by looking at the food in your hand, you can not figure out its ingredients (unless there is a litmus test for everything :)) Well, you are in luck, because FDA mandates Food Labeling for food and drug items. Now, you can view the ingredient list on back of the food container and be assured about its bill-of-material.

For software products (say a python package or a container image) that’s (well) exactly the same. As a consumer, when we are using any third-party software product, we need a way to verify its ingredients. And as a producer, we need a comprehensive tooling to generate that ingredient list while building those software products. And that list would be a software bill-of-meterial or as commonly known as SBOM. In this blog, we will focus on producer part of the equation around tooling to generate SBOM for micro-services.

What we can expect from SBOM?

Let’s first list desired properties for SBOM: (without claiming that this bill-of-desired-properties is complete :))

-

Automated: Well, ofcourse we can not ask (or not rely on) developer to possibly know every software dependency (and their transitive dependencies) while they are writing code. SBOM generation should be automated process in the software build/delivery lifecycle.

-

Complete We don’t want to miss ANY software dependency while we are discovering it.

-

Accurate That’s the whole idea behind the SBOM, isn’t it ? For every software dependency we should be able to uniquely identify it’s source and version.

-

Interoperable Right, we want SBOM in some standard format that can be validated/transferred/audited/parsed or in other words operated independently.

-

Verifiable Need to make sure we can distribute SBOM securely and consumers can verify the integrity of the SBOM.

SBOM for container micro-services?

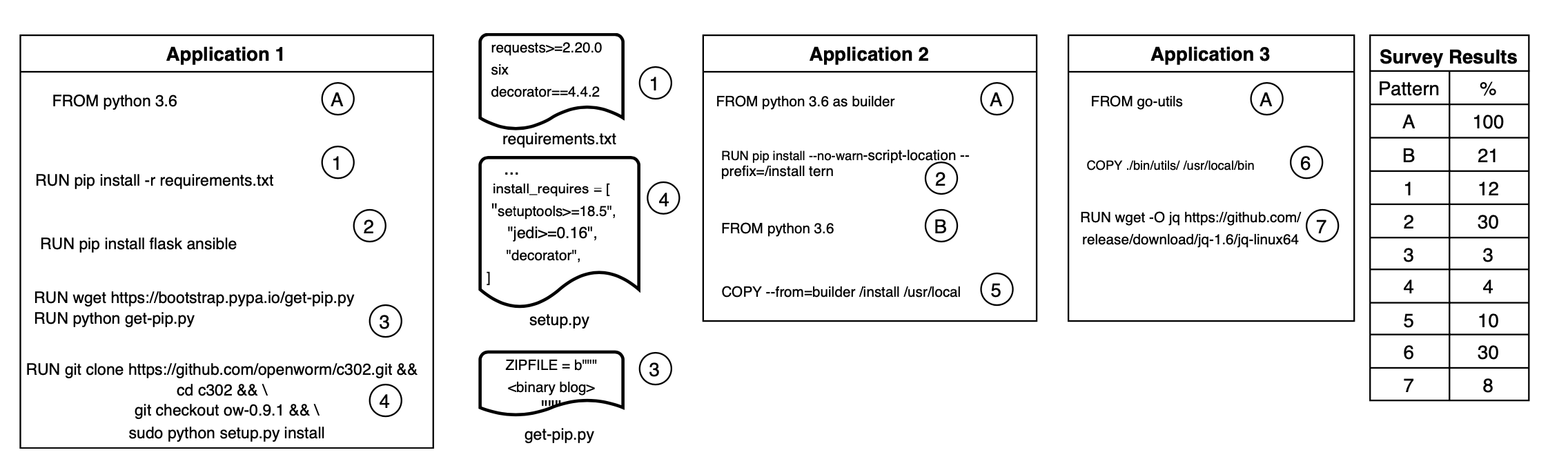

For micro-services a deliverable software product is commonly a container image and is typically build through recipe defined in a Dockerfile. The Dockerfile allows developers to express different patterns and strategies for building their applications. To understand common practices, processes observed by developers and operations teams we surveyed open-source micro-service application repositories. From the set of all repositories on github.com, we filtered the ones containing atleast one Dockerfile and then ordered them by their popularity based on number of stars. We then scanned these repositories to learn and categorize various developer patterns. Survey results discussed below are based on top 100 Dockerfiles and top 100 python micro-services.

We observed atleast 5 different patterns (1-5) developers are practicing to define and install just python dependencies for their applications, and 2 other patterns (6-7) to install third-party dependencies. As we can notice, there is a lack of standard practice in declaring the open-source dependencies that makes their provenance tracking even harder. At image level there is a single stage build pattern (A) wherein all dependencies are installed and delivered in the same image, or an use multi-stage build (B) to install dependencies in separate temporary image and copying them to final image (5). Also, these dependencies can be installed through standard package managers (1,2), or compiled manually (3,4). Furthermore, these dependencies can be managed in separate package manifests (1,4) or installed on-demand (2). In other cases, dependencies are baked into an image by copying pre-compiled binary from local build environment (6) or from well-known hosting repositories (7).

Therefore, SBOM discovery limited to discovering packages by quering package managers (pip list, apk list) is Insufficient as it does not cover bases for other modalities of dependencty inclusions. There is a need for a comprehensive discovery engine that could account for all these modalities.

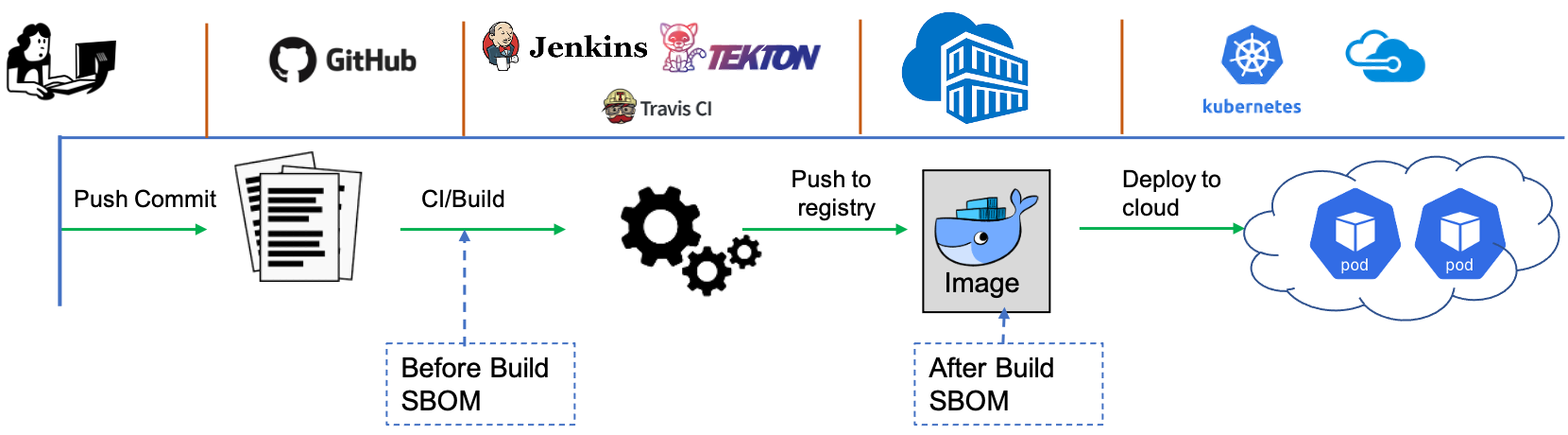

Next, another important dimension to consider is – “When to compute SBOM?”. As illustrated in a very simplied lifecycle of micro-service lifecycle above, SBOM can be computed in the DevSecOps pipelines before building the image or from the image after it is built. Let’s argue about both these options.

SBOM in DevSecOps pipelines before build

At this stage, SBOM is computed from various build artifacts (including package manifests) available in the git repositories, like Dockerfile, requirements.txt, pom.xml etc. With access to all the source artifacts, we can perform deep provenance checks on all the dependencies, reason about “how it is installed”. For multi-stage builds, we can scan every build stage independently for completeness. Also, for statically-linked applications like go apps we can precisely understand their dependencies from their dependency manifests like go.mod.

Although, this SBOM is still speculative, unless we can ensure every dependency in this SBOM is the one that gets installed during the build. For instance, in the survey we mentioned above we noted in 91% Dockerfiles, base images were tagged with moving tags or partial versions. For open-source packages, over 1333 aggregated unique packages across all python applications, 25% of python packages were not tagged with any version and 40% packages were tagged with version constraints (minimum/maximum version range). In such cases, when software dependencies are not pinned precisely, their versions are resolved automatically at the build time. For instance, a base image specified with moving tag, like golang:1.14 will get resolved at build time to the latest available version from [1.14.9, 1.14.10]. Similarly, a package with no pinned version will resolve to the latest available version at the build time.

SBOM from an image after build

Well, then compute SBOM from the image. Well not that simple :) Turning pros from above option to cons here – in case of multi-stage builds, the dependency inventory of the build stage(s) is not available. Also, for micro-container images containing a single statically-linked binary (go-app) its challenging to discover dependencies.

So what do we do ? Maybe we can take following approach:

- Compute SBOM before image build in the DevSecOps pipelines

- Lock/freeze all the dependencies before build from the SBOM

- Use this locked version during the actual build

- Generate SBOM on the image after build and verify it is a complete subset of the

previousSBOM.

In the next blog, we will dive in more details on this approach. We will also discuss about (existing/emerging/desired) SBOM standards, existing set of tools and automations ready-to-use. Another important topic would be build vs deployment SBOM, because not every image that is build gets deployed.

Please ping/email me with your feedback and suggestions.